Stupidity Defined

Not long ago, I was lurking on social media and - as always - a "political" argument started - but these arguments are never really political, are they? Anyway, somebody said, "That's stupid," to which somebody else said that to use the term "stupid" is ableist. So I guess nothing is stupid. Cool. Fine.

But... what if we were to define stupidity as any avoidable thing which inhibits one's ability to work with - and, therefore, gain skill and experience and knowedge of - the material world? And, what if we, in turn, understood the material world to be that which exists beyond one's symbolic constructs, including that specific construct known as language?

In that case, stupidity is not a matter of a person having a low I.Q. - it's not really primarily about a person at all. It's, if you like, about something happening to that person. Any avoidable obstacle for dealing with the material world would then be stupid - and all kinds of things can be obstacles.

Now, notice that I say, "avoidable" - a quadriplegic may have difficulty in certain activities, working with the physical world, but that doesn't make them stupid. And even if, for instance, a person who has a form of deafness that could be "cured" through a cochlear implant, we shouldn't assume that it's stupid for them not to get one - they may be attaining all kinds of experiences and skills that normally hearing people cannot, and so the trade-off might not be worth it.

Rather than stupid people, we would speak, perhaps, instead, for instance, of stupid ideas. And anyone, regardless of their I.Q., can have a stupid idea. So people are not inherently stupid. Yes, stupidity is, in a certain sense, about a person's ability, but to tell a person that they have a stupid idea is not to say that they are mentally incapable of understanding the truth, but just the opposite: that something that is happening - perhaps something they are doing - perhaps an idea they are asserting - is artificially preventing them from achieving their potential. In a strange way, it's almost a kind of compliment. It means: I believe in you. Cast off this useless husk of a concept, which is not adroit or limber enough to cover the current predicament, and which is only muffling your ability to feel the world's texture, and I am sure that you will confront reality more creatively and effectively.

Moreover: any idea can be a stupid idea. Sometimes I think that maybe ideas are just clusters of concentrated stupidity. In which case the least stupid person would be the person with the fewest ideas. But... nahhh. Any idea can be a stupid idea, but every idea doesn't have to be a stupid idea. They only become stupid if we focus on them too dogmatically, in such a way that they prevent other ideas from getting in.

So ideas are not inherently stupid, any more than people are inherently stupid. It depends on how you hold them. If one grips one's fist around an idea, ever more tightly, it will be difficult to pick anything else up. But if one juggles ideas, always maintaining some awareness of each idea as they pass from hand to hand, through furtive glances and sense of touch, then perhaps another idea may be added and kept up in the air.

...But then again... maybe not! I am fascinated every time I come across a dogmatist - a Fundamentalist Christian, or a Leninist, or an Ayn Randian Objectivist or Rothbardian or what have you, that comes across a piece of information that doesn't fit into their worldview. They often have to perform a set of mental gymnastics in order to maintain their worldview while this annoying truth is obnoxiously sitting their in front of them. It often requires a great deal of creativity - of subtlety - of ingenuity - of nuance - of dexterity - of intelligence - of grace - to accomplish. It clearly requires the very opposite of stupidity, and makes the open-minded person seem lazy by comparison. At the end I can only applaud. Perhaps open-minded people are the ones who are really missing out on the joys of evasion and circumlocution.

Any idea that says that certain ideas are forbidden is prima facie a stupid idea. That is to say - on first impression, it is a stupid idea, because it seems like it probably involves blocking out some part of material reality (like the people and books that say it).

It might not be a stupid idea! (Don't forbid it!) It may turn out that keeping certain ideas out - perhaps certain stupid ideas - is necessary for us conscious machines to function. But to find out, we will have to

investigate - which means violating the taboo against entertaining this

idea. Hm.

By this token, anything that says that certain words, or

expressions, or thoughts, or feelings are forbidden is also, prima facie, a stupid idea. So censorship looks pretty stupid. But then again, the avalanche of information that paralyzes us by overwhelming us seems pretty stupid, too. Hm.

It's looking more and more like (some of) the very things that can be difficulties and obstacles to engaging with and working with the material world can also be the solutions to these difficulties.

So, in that sense, not only are there not any stupid people - or no inherently stupidly people, anyway (we're all a little stupid, each in our own way, and as tiny, finite beings in an incomprehensible universe, we're all collossally, cosmically stupid); there are no stupid ideas, either - or at least not any inherently stupid ideas. I suppose this is in the same spirit that people say, "There's no such thing as a stupid question." Well, there are stupid questions, actually, probably. There may very well be questions that, in the very phrasing of the question, obscure or prevent access to a broader understanding of the topic at hand. But they're just not the type of questions that people generally think are stupid questions. People think that they are betraying their ignorance by asking very basic questions, but the basic questions are actually the most important, deepest, and often the most difficult to answer. For instance, "How many joules are in a watt?" is a slightly stupid question, because it makes some false assumptions. But "What is a joule?" is a much better question, a much less stupid question, because it is more basic. And "What is energy?" is very basic, and therefore very profound, and very, very difficult to answer. It is the opposite of stupid.

Now, again: in a certain sense, this means that there are no inherently stupid questions. It depends on how we ask them, and how we answer them. The stupidity comes in when the questioner demands an answer that follows the rules of the question. So, for instance, when a person asks, "How many joules are in a watt," and someone else responds that these units measure different things, energy and power, and that power is proportional to energy divided by time, and so on and so forth, if the questioner then demands, "Yes, but you're avoiding my question: how many joules are in a watt? I want a number!" then we are running into some stupid language games. Rather than demanding that the answer stick to the rules of the question, we should simply say: "Ask me in the way that makes sense to you, and I will answer in the way that makes sense to me."

...Because, you see, this is a big part of the game we are playing here. Probably the most important part of working with, and gaining skill and knowledge of, the material world... is working with other people, and developing one's skills of interacting with people, and learning from people. We do this in a variety of ways, including language, which in turn includes having a conversation, which in turn includes asking people questions, and answering questions. Of course, there's more to life than this. But people are some of the most important parts of the material world, in part because through them we can learn more about the material world, including learning more about people, and learning more about learning. And demanding that everyone play your game according to your rules all the time... is not an especially skillful way of interacting with people. Partly because you learn less when you insist that people give you only the answers that you want. Your loss, not theirs.

What kinds of ideas prevent us from working with, and learning from, the material world? (And by "world" here, I mean "universe," of course.) Here are two big bowls of them: one is the idea that there is no material world - that there is nothing outside of our symbolic constructions, including language. There is no truth, no absolute reality, etc., etc., etc.. The other is that there is a material world, an absolute reality, and that you already know what it is. If one were to make either one of these assumptions the basis of one's actions, it would make one epistemologically lazy.

(By the way: I could be wrong about this, but I think these two big bowls of stupid are just two versions of the same thing. I think the person who says that there is no material world - that there is nothing outside of symbolic constructions, etc., etc., is being very dogmatic. They are just one version of the person who dogmatically says that they know the absolute truth. They are, in effect saying, "I absolutely know what reality is: it's nothing. It's not even nothing. It isn't anything. It is not." ...to which I reply, giggling: "How do you know?")

Notice what I am saying, here, and what I am not saying. When people say that there is no material world, nothing outside of symbolic constructions, etc., I am not saying that those people are wrong. And when people say that there is a reality outside of their symbolic constructions, and that they know, for certain, exactly what it is, I'm not saying that those people are wrong, either. They may be right! I'm not saying that these are wrong ideas - only that they are stupid ideas. That is to say, they are ideas that make us stupid. A much less stupid attitude is to assume that reality exists, but that you don't know what it is, and that you're going to try to find out. Which might be wrong! This might be wrong on all counts - you might be wrong about yourself, for instance - you may not actually be trying. Or reality may not exist. Or you might actually already totally comprehend reality, absolutely and completely. But it's still better, and less stupid, to assume that you don't. It's better to be smart and wrong than to be stupid and right.

Always assume that "Something is happening, and you don't know what it is... do you, Mr. Jones?" Always be Mr. Jones.

And here are some more things that I'm not saying. I carefully said: "if one were to make either of these assumptions the basis of one's actions" - which, practically speaking, never happens. I'm not saying that people who claim that there is no reality outside of language (etc.) are epistemologically lazy. Because, frankly, I don't believe them. By and large, I don't think they actually live their lives the way a person would in a world where there were no reality outside of language. And by the same token, I don't think that people who claim to have access to the absolute truth generally really behave like they know the absolute truth, either. Perhaps it's too uncharitable to say that both of these groups of people are lying to us, but perhaps it's possible that they are lying to themselves? I'll put it this way: both of these groups of people are less epistemologically lazy than they claim to be, although all of us are more lazy than we should be.

"Should?" That's another thing: morality is, by and large, pretty stupid. Perhaps it has to be. If one were to empathetically try to understand every point of view, it would quickly become impossible to make any moral judgments at all. So one has to block off certain aspects of reality in order to live a moral life. And that's fine. It's okay to be stupid. In fact, it's good to be stupid, in some ways. You should be stupid.

When I say that we are all more lazy than we should be, and that it's better to be smart and wrong than to be stupid and right, these are not moral judgments. I'm not saying it's morally better to be smart and wrong. I'm just saying it's more advantageous for you to be smart and wrong than to be stupid and right.

How do we avoid being stupid? Through science. "Science" may be defined as the sum total of tricks that people have devised to avoid being stupid. But, although I have many disagreements with Jeremy Bentham, one habit of his that I particularly like is when he writes, "art-and-science," hyphenated, just like that, because for him, art and science were one thing, inseparable, and science is mostly art. The way I would put it is: science is an art. Not all art is science, but all science is art, and appreciation of science requires an appreciation of art.

Work, practice. How do we avoid being stupid? By making mistakes. By being wrong. How do we avoid being stupid? By being stupid. Don't prevent us! Don't take away our ability to be stupid! Let us be stupid!

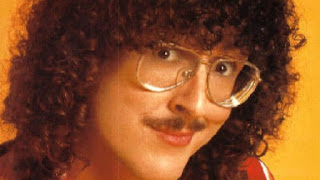

Forget Sapere Aude. With Weird Al Yankovic, I say, Dare to be stupid.

Comments

Post a Comment