Why Capitalism is Ending

THE PRODUCTIVITY BOMB

Sorry, Ray Kurzweil, there will be no singularity. As much as Moore’s Law has become a cliche, it has also become a cliche to point out that exponential growth has no "knee" - that is to say, that an exponential growth curve has no inflection point. It goes up faster and faster, so that not only is the value rising but the derivative of the value is also rising (that is, the rate of increase is itself increasing) yet at any given point it is still a gradual increase. Growth that gets indefinitely huger as it approaches a specific point of time, a limit known as a singularity, is not exponential growth but rather hyperbolic growth. There’s no evidence that technology is growing hyperbolically; it is “only” growing exponentially. Gordon Moore himself has stated that he doesn't believe in the singularity, or even in the continuation of Moore's Law. (And Moore's Law is starting to fail, anyway... ) But it hardly matters; the rate of technological growth is still really, really fast.

All of this having been said, exponential growth (or even slightly sub-exponential growth) is enough - enough to utterly transform the ways that we work, the ways that commodities are produced and distributed, the kinds of services that are provided and the format in which they are provided, the entire economic system, the social relations of the people in that system, our global class structure and all of our cultures and political systems, and - who knows? - probably our art and religion and philosophy and everything else that humans do.

That Was Before We Turned

Just look at that beautiful curve. For a while.... millions of years... humanity was going one way. And then it just... turned. Changed direction. With no clear way to ever turn back. Centuries later, we will look back at everything before the 1970s (or the entire span from the late 50s through the 21st century) and say, "Yes, but that was before we turned." There is no "knee" to this curve, but there is a curve.

We've been going that other direction, since the 70s, ever faster and faster.

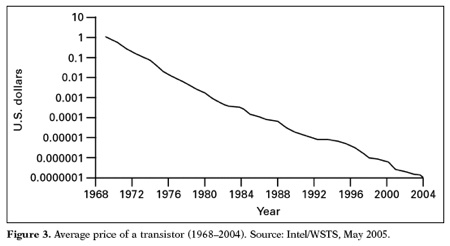

At the same time that transistors have been multiplying and computing speed has gone way up, the cost of transistors has gotten exponentially lower:

...So that a computer chip that contained 2,000 transistors and cost $1,000 in 1970, $500 in 1972, $250 in 1974, and $0.97 in 1990 now costs less than $0.02. A personal computer that cost $3,000 in 1990, $1,500 in 1992, and $750 in 1994 would now cost less than $5.

These kinds of mind-boggling statistics are the reason why we cannot meaningfully extrapolate from economic experiments of the 20th century onto economic realities of the 21st century. The exponential rate of the progress of technology and of the changing economy that it drives means that 1917 has more in common with ancient Greece than it does with 2017, and 2037 will have less in common with 2017 than 2017 has with 1917. Bolshevism, for instance, simply has almost nothing to do with the contemporary world, in a positive or negative sense. That was before we turned.

Some areas of science and technology are actually progressing a good bit faster than Moore's Law would predict. Behold, the price of genome sequencing:

Source: Fortune Magazine

Of course the ultimate technology to watch in this regard is artificial intelligence, because eventually machines are going to become able to improve themselves - and once that happens, they could bootstrap very, very quickly. On the one hand, Cliff Young of Google tells us that Moore's Law has ended, the growth curves have already leveled off, and he projects that we should not expect a doubling of processing speed until 2038. On the other hand, he also tells us that this plateau is merely the calm before the storm. Deep Learning is expanding at a "super-Moore's Law" rate: "The number of academic papers about machine learning listed on the arXiv pre-print server maintained by Cornell University concerning is doubling every 18 months. And the number of internal projects focused on AI at Google, he said, is also doubling every 18 months. Even more intense, the number of floating-point arithmetic operations needed to carry out machine learning neural networks is doubling every three and a half months." Google, he says, has been "an AI-first company for the past five years." He himself calls this "a little bit terrifying." (This is part of the reason that I'm much more worried about Google having too much power than I am about Donald Trump.)

Cue the arguments about whether computers can ever truly be conscious, whether they can laugh, or love, blah blah blah. If you're going to argue about this, and trot out Searle, and Chalmers, etc., etc., etc., you're missing the point. The question is not whether machines can ever be self-aware, or intelligent, or whether they can learn to do everything that humans do, or even whether they can ever achieve superhuman intelligence.

THEY ARE ALREADY SUPERHUMAN. A pocket calculator - or for that matter, an app on your phone - can calculate square roots and logarithms faster than any human. But it's not just simple arithmetic: this applies to the highest levels of math as well. They have produced mathematical proofs that no human can comprehend. Computers can beat humans at chess and go and checkers and Space Invaders and the Rubik's Cube and poker and a hundred other games, and this list is growing exponentially faster and faster. Their memory lasts much longer than our memory, preserving original data whereas our memories are mostly reconstructive and sometimes pure confabulation. And even if the memories are in there somewhere we can't always bring them out - they stay on "the tip of the tongue" - whereas computers are getting vastly superhuman in their capacity for search and recall (search is Google's specialty, of course....). They can scan through trillions of pages of documents in fractions of a second. Their perception is better: they have cameras that can see in micrometers or across lightyears, in "colors" (so to speak) of the spectrum that we will never see. But more importantly: their reasoning is more logical and more statistically valid than humans. As they get smarter, they are far less likely to fall prey to the myriad cognitive biases to which humans, let's face it, always will. Besides, they have the advantage that they can focus all of their attention on a single problem, for as long as it takes to solve it. They never have to sleep, or smoke a cigarette, or go to the bathroom. They never form unions. They don't need health insurance or other benefits. They never create unnecessary conflicts, petty rivalries, or sexual scandals. They obey. Job after job, in a fair match between a machine and any human being competing for a position, the machine will win.

What matters is not whether they can make a joke, or compose a sonnet, or write a song (although of course, they can do all of those things). What matters is whether they can improve themselves - write their own code, and rebuild their own hardware. Because once that starts, the looping self-improvement will just get faster and faster. And that's already starting to happen.

In the 70s, a person could buy a kit to build her own computer, and then assemble the entire software, from the operating system all the way up to applications and documents herself. But things are more complicated now. Teams of developers work on every component, so that no one person completely understands every aspect of how an operating system works, let alone all of its software. In fact, most of that information is well-guarded, proprietary information. Meanwhile, in the age of the internet, everything is deeply networked. So each individual user is only seeing a tiny sliver of the whole picture. A piece of software is not developed by a single person, but by a team using an engine developed by earlier teams and in a deep symbiosis with existing technology. Coders are now working in IDEs (Integrated Development Environments) that assist the developer in countless ways, and which are getting more and more sophisticated every year. Soon most developers will be utterly dependent on their environment assisting them in every aspect of coding.

And we are already beginning to see the next step: the U.S. Department of Defense, in collaboration with Google and Rice University, recently unveiled BAYOU, a deep machine learning algorithm that works together with developers, and it is learning to write code. We can expect more code-writing algorithms soon, competing with BAYOU, to be the best product.

It's no wonder Stephen Hawking said that the emergence of AI could be "the worst event in the history of our civilization". But it's also no wonder that he modified that a few days later to say that the real problem is not artificial intelligence, but class structure:

"If machines produce everything we need, the outcome will depend on how things are distributed. Everyone can enjoy a life of luxurious leisure if the machine-produced wealth is shared, or most people can end up miserably poor if the machine-owners successfully lobby against wealth redistribution. So far, the trend seems to be toward the second option, with technology driving ever-increasing inequality."

-Stephen Hawking

"Singularitarianism" (ugly word) isn't materialist. But you don't have to buy into Kurzweil's hocus pocus - shilling for supplements, wondering whether Jay Z is a time traveler, etc. - to see that we are in the midst of a long-term productivity explosion. I agree with Kurzweil that, looking at this data, I see not just a quantitative change, but a qualitative change to the human experience. History has become obsolete; nothing about the past can prepare us for the radically different future. (That's why any comparison with redistributive schemes from the 20th century is completely beside the point - that was before we turned.) We are now entering uncharted territory, and may be past the point of no return. But - maybe due to my native pessimism and misanthropy - where Kurzweil sees the advent of utopia, I see danger and causes for concern. I'll admit it: I'm scared. When you look at the flip side of these charts in which we're suddenly scaling mountains, we've just fallen off a cliff.

Everywhere we are faced with what is growing to be more and more undeniably apparent - planet Earth is now transitioning to a new mode of production. And a new mode of distribution, to boot.

* * *

Look around.

I’m a musician. I've had a few music-related jobs. I’ve been watching the music industry gradually (and sometimes not so gradually) collapse for thirty years. In the 80s, the industry complained that home taping was killing the industry. In the 90s it was Napster. Nowadays, anyone that can use a mouse can listen to billions of songs on Youtube (owned by Google's parent corporation, Alphabet). People are sharing everything. I'm not saying that's a good thing. On the contrary, I think it can cause many problems, both short-term and long-term. What I'm saying is, it's happening.

But music is only the canary in the coal mine. It's not that hard to find websites in which one can watch movies for free - even movies that are still in theaters. Millions of people are streaming television shows without paying.

And then there's books. Just go to Google, type in the title of the book you want to read, and then the letters "pdf". If you don't find it immediately (and I mean, within a fraction of a second), you can go on social media and ask around for a copy. It won't be too hard to find.

Pirated video games have been a thing since I was a kid. And here we get to the meat of the matter. In this "information economy," when software itself can be - and is - replicated endlessly, what is the incentive for consumers not to share it? And if people won't pay, then what prevents this industry from being a bubble, ready to burst at any moment? (Of course, the dot-com bubble of the 90s was just such a situation and we can imagine the rueful glee that music executives took in watching the industry that had just eaten their lunch get its comeuppance.)

Okay, musicians, artists, software developers, and their industries... everyone knows they are in trouble. Who else? Anyone dealing in information. Doctors. In fact, not just doctors - as I write this, the entire healthcare industry is being transformed. And that matters, because in this service economy, for many communities the healthcare sector is the number 1 employer. Machine learning algorithms, capable of identifying patterns in visual information, are now detecting cancer. Not only can software make diagnoses, sometimes more accurately than their human counterparts, but robots are performing microsurgery. Right now, Deep Mind - the same research group that developed AlphaGo, the machine learning algorithm that beat Lee Sedol at Go, (and which has been acquired by Google) is partnering with the National Health Service in England and has already developed an app that is transforming healthcare there (and leaving our pathetically antiquated American healthcare system in the dust). However, they also got in trouble for not protecting sensitive patient information properly. Who knows where that story is going?

Lawyers. A 19 year old kid developed what he calls a "robot lawyer" - a free chatbot that has helped people get over 160,000 traffic cases overturned. And in England, Case Cruncher Alpha recently turned out to be more accurate than 100 lawyers, by a margin of a whopping 86.6% to 66.3%. Already, the California Judicial Council is recommending replacing judges with computer algorithms, understandably, since human judges have been found to be more lenient in parole hearings after they've had lunch.

Why not? After all, we are being judged by machines all the time. The worldwide surveillance apparatus feeds into digital minds that are continually sifting, collating, and processing this massive amount of information - everything from the products we buy, to the things we look at on the web, to our faces and voices being recognized by the cameras and microphones in everything. In China, this allows them to assign a "social credit" score to each person. On this side of the world, machine learning credit algorithms already determine whether or not we get loans. In fact, the entire financial world has essentially already been assimilated by algorithms. The traders we see jumping and yelling on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange are mere bit players. The real trades are being made at speeds of millions per second - by software, to software, through software. (Spread Networks, part of Zayo Group, LLC, bore inch-wide holes through Allegheny mountains to lay ultra-fast fiber optic cable, so that they could shave a mere 3 milliseconds off of every financial transaction - an enormous amount of time for an algorithm, and enough to provide a substantial competitive advantage.) They have already taken over Wall Street, which means they have taken over the world. Humans lost control years ago and almost no one even noticed.

But the big information dealership that is destined to go down is the world of education. The dot-com bubble was bad, the cryptocurrency bubble was bad, and the housing bubble seemed like the worst thing since tulipomania, but none of them are in the same ballpark as the education bubble. Education is so overvalued at this point that we essentially all live in the education economy, and we're all stomping on the Hindenburg. In iceskates. This will be a crash like no other crash before it, because for several generations now, an education has been the dividing line between classes, the sociological marker of membership in the middle class. Education matters even more than income, because education is the most important determining factor for a person's social capital (it's not just what you know, it's who you know). It is this precise form of social relation that allows a class to constitute itself as a class, and not just as a bunch of people who happen to have stuff. Of course, as we learned in recent elections, the division between the educated and the uneducated also matters more on a political level than anything else, including income.

Yes, all the information jobs are in trouble... but what about "real" jobs? Well, they've been in trouble for a long, long time. Obviously, automation is taking a huge bite out of industrial work, and now agriculture, too. Now taxi drivers have been replaced by uber drivers - next, uber drivers will be replaced by self-driving cars. And then it's the truckers' turn. And the bus drivers' turn. And who knows who is next?

(By the way, this is one reason why we'd better focus on the welfare of artists and other "creatives" - because we'll all be creatives soon. Creative jobs will be the only jobs available... and even they will be taken over by machines soon after.)

We can tell ourselves that "knowledge" jobs are leaving, but "wisdom" jobs are here to stay, and we can even print that out on Hallmark cards and pass them to each other, and maybe that will make us feel better. But the fact remains. Every single industry, every single sector of the economy is going to be transformed - so totally transformed that we might as well say "destroyed". And it’s happening very quickly and it’s going to happen faster and faster.

Of course, all of the above will accelerate massively with the development of nanotechnology.

But the catastrophic shift that is happening all around us, in obvious ways and in ways that we barely notice, can be summed up in a single sentence:

Every economic system that has ever existed on Earth until now has been based, for the most part, on human labor power, and soon that will not be true anymore, ever again. That one, undeniable fact changes everything.

In Praise of Capitalism

I hope it's clear from the above examples: my point about the end of capitalism is not moralistic. I am not saying capitalism is bad or evil. On the contrary. Every time I pass a storefront and I can see that they've gone out of business, my heart sinks a little - not only because of the jobs that have been lost, and the families that will be experiencing deprivation and dislocation, but also because I can't help thinking, this was once somebody's dream. And now it is gone, probably forever.

Capitalism is not only the most efficient and productive economic system that has ever existed, it's also the one that gave rise to political rights and freedoms such as never existed before. Yes, it also involved exploitation, bloodshed, misery, imperialism, war, etc., but under capitalism average lifespan has increased, famine has decreased, poverty has decreased, many otherwise debilitating diseases have been treated, prevented, and eradicated, literacy has increased, etc., etc., etc.. By almost any measure, it's been a good run.

Not only that. It's not just that capitalism is "good" according to some standard that exists above and apart from capitalism. The reality is far more radical: capitalism actually created the very standards by which we judge capitalism - values like freedom and justice, as we currently understand them - almost as by-products, or even waste-products, of its production process and relentless innovation. By its own standards, it has been great (of course). But also, even by its own standards, it is starting to fail.

There's an old saying among psychologists: neurotics build a castle in the clouds; psychotics live there. Similarly, we can say: those who imagine some future state in which all of the social contradictions have been resolved, which will be so equal and free and balanced and peaceful and stable that it will last forever - those people should be called "utopians." And we should reject their nonsense out of hand. But what about people who think we already "live there"? People who think that we have reached "the end of history" - who think that capitalism itself is so stable that it will last for eternity - aren't they even more utopian, even more delusional? There should be a word for that.

Things come and go. The feudal mode of production came and went. Yes, industrial capitalism - the bourgeois mode of production - has held sway for centuries.

But nothing lasts forever. All things come to an end. And capitalism is no exception.

And I’m not making a moralistic point on that end, either. I’m not saying capitalism is wrong or bad, but I’m also not saying that the end of capitalism is something wrong or bad - or that it’s good for that matter. All I’m saying is, it’s happening. Let’s not put ideological blinders on and pretend that it’s not happening. I’m saying, we’d better start planning now to figure out what we’re going to do once capitalism is over. Because once this system completely collapses, it’s going to be too late to say, “Gee, I guess we should have planned for this.”

This is, by the way, where I part company with Marxists. Marxists think that capitalism will end, and I agree. But they seem to assume that what's coming next will automatically, necessarily be better than capitalism. Again, this might be the pessimism talking, but I'm not so sure. Sure, what comes after capitalism might be better than capitalism. But it might be just as bad as capitalism. And it might be a whole lot worse. We may be facing a class structure far more stratified and rigid than that of capitalism, with wealth and power concentrated among even fewer hands... and it may last a lot longer than capitalism did. But whatever it is, what's certain is: it's coming. So we'd better start planning, and organizing, for the post-capitalist future that is coming whether we like it or not.

The Means of Production

When we used to talk about the "means of production," not very long ago, this meant a lot of different things, but primarily it conjured up for us images of the factory system. (Plenty of lefties even today seem to think we still live in that sepia-tone world, with newsboy caps... and their habit of growing old-timey facial hair and affecting little spectacles is a perfect representation of their fundamentally reactionary stance.)

Nowadays, the means of production may simply mean a single person sitting in front of a single computer. One person can easily produce on a personal computer, installed with Photoshop, with a photo printer, what would have taken several roomfuls of people painstakingly setting moveable type on a printing press, separating colors in photographs for CMYK color processing, and so on. That single worker produces all that a larger number of workers formerly could produce, and probably a few things that they couldn't produce. That's a massive, massive increase in worker productivity. That's great news... unless you're one of those people who used to have one of those jobs.

Honestly, I'm not sure it's good news for anyone. The factory system can be extremely oppressive, exploitative, dehumanizing, and debilitating, especially for the workers. But there was a positive side of the factory system for the workers, as well. It brought workers together and organized them and revealed their own power to themselves. To put it differently, it socialized production. It only took a catalyzing spark for the workers to realize their control of the means of production through work stoppages, sit down strikes, wildcat strikes, general strikes, and often violent conflict with the paid goons of their exploiters. In America particularly, in the late 19th and early 20th century, the owners' brutal suppression of this struggle was especially violent.

But in the post-factory era, our new organizations of labor are - at least on the level of physical space - more atomized and alienated than ever. Organizing for a general strike, though a romantic, nostalgic good time, will face new challenges in the 21st century. I personally am a proud union member, but I have to admit that unions have precipitously lost power, due at least in part to fundamental tectonic shifts in the economic forces that govern us more totally than any government, and there is no obvious reason to think this trend will be reversed.

Not only is the worker's relation to other workers changing, and deteriorating, in such a way that deincentivizes solidarity - but also, the worker's relation to her own work is changing. For one thing, as technology predictively adjusts to our every need and provides us labor-saving innovations, making our work easier and more efficient, it is also deskilling our work. Deskilling has a similar effect on our power relations that the collapse of the factory system had: it makes us more replaceable, and thus less valuable, and thus takes away a lever we once had in negotiation.

What is Destroying Capitalism?

Unions and other forms of worker power and labor representation, embattled as they are, are not the force that is destroying capitalism.

So what is destroying capitalism? Is it some kind of conspiracy, the Bilderbergers and the Rothschilds meeting with Van Jones and George Soros in the basement of Comet Pizza? No.

No government can destroy capitalism. No political party can destroy capitalism. (Read those sentences again.)

It's not war that will destroy capitalism. It's not protest movements that will destroy capitalism. It's not moral values that will destroy capitalism.

What is destroying capitalism is - capitalism. Capitalism contains, within itself, forces set in motion that will eventually destroy capitalism. There's no way to prevent this process, and no way to stop this process once it's started.

Right wingers like to imagine that the end of capitalism comes when some kind of authoritarian government comes in and clamps down on the "free market". But precisely the opposite is true: the state works for the interests of capital. The example of people illegally downloading demonstrates that the real danger for capitalism comes not from any government restriction but from the people being too free. When the government is powerless to enforce property rights - as, clearly, they are, at least for every single song on youtube - capitalism has already lost.

Government is slow. The pace of technological change is fast, and getting much, much faster. Already our property rights laws are woefully antiquated. As technology speeds up and speeds up, government - especially democratic government, mired in relentless gridlock - will be increasingly outpaced and will consign itself to irrelevance. Perhaps this is part of the reason why people all over the world are desperately turning toward authoritarian governments - governments, they hope, that can "get things done". But it's hopeless. All government, no matter how authoritarian - indeed, all human activity - will inevitably lag further and further behind the pace of technology. No government will be able to "bring the jobs back." Already governmental politics is becoming a meaningless spectacle. And any revolutionary change would just bring in a different meaningless spectacle.

When the government is powerless to enforce property rights - as, clearly, they are, at least for every single song on youtube - capitalism has already lost.

But it’s fascinating to see why capitalism is collapsing - it’s because capitalism is too productive. That sounds confusing - it sounds like a contradiction and maybe it is. But our entire capitalist system is premised upon scarcity - more specifically, the assumption of scarce goods. That’s the fundamental axiom upon which the entire edifice of our economic system is built. And there have been problems with that for decades if not centuries.

That’s why capitalism requires systems of manufactured scarcity, which can be summed up in the following phrases: if a good isn’t scarce, then make it scarce - by force if necessary. That’s why we have things like the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which paid farmers not to grow crops, or other programs that exist to prevent farmers from selling the crops they grow. The central planners knew that if all the farmers were growing at full capacity, and bringing all that food to market, there would be too much food, which, by the law of supply and demand, would make the grain prices drop, which would bankrupt farms. It's because of this artificially created scarcity that, in the "rational" and "efficient" world of capitalism, food rots unused in silos while, at the same time, people starve. There’s so much unused grain in silos that people die every year, literally drowning in grain. This phenomenon, known as grain entrapment, happens every year. It’s not uncommon for, say, about 50 people in a year to fall into these huge piles of grain, so that they can’t get out - thus living out the perfect metaphor for our entire economic system.

And this is

not just a matter of farming - in industry after industry, there’s a

super-abundance of products, and we have to artificially create a

scarcity of products to keep the economic system working. This affects

international trade, for instance: we’re all familiar with the concept of "dumping," in which a

country supplies our consumers with too much of a product, which

undermines the price, putting a lot of local producers out of business.

So the government tries to put up barriers to trade, to prevent all

these cheap goods from entering the country. But all of these - usually government-imposed - strategies

we use to try to create scarcity, to prevent consumers from getting

products for free or inexpensively, are only, at best, stop-gap measures. They

cannot win in the end.

By the way, the planners that are responsible for manufactured scarcity are not just in government. For instance, another example of manufactured scarcity could be the oft-cited planned obsolescence, planned not by government bureaucrats but corporate bureaucrats (ultimately, what's the difference? A bureaucrat is a bureaucrat) to attempt to artificially gin up demand for a new product every few years. (I'll admit that this form of manufactured scarcity is more questionable - after all, it's inevitable, given the rapidly accelerating pace of technology, that products will become obsolete, and people can hardly be blamed for planning for this. Still, every few years, when Apple periodically changes all of their input jacks and connections - Apple jacks, haha - isn't it obvious that they're aggressively pursuing proprietary exclusivity?)

There’s no way to stop or slow down this

massively growing productivity that undercuts the entire economic

system. As in everything else, government action will simply be outpaced here. It cannot possibly hope to catch up. The movement of technology is too fast, and more importantly too complicated. That's part of the very nature of the progress of science and technology: it can't be predicted. If you could predict future science, you'd already know it. But you don't know it, until you figure it out.

You don’t have to be a left-wing radical, thumping your fist about some future “post-scarcity economics” to realize that productivity is the underlying problem here. Back in 1999, Alan Greenspan, in his characteristically subdued tone, mentioned that:

"It is the observation that there has been a perceptible quickening in the pace at which technological innovations are applied that argues for the hypothesis that the recent acceleration in labor productivity is not just a cyclical phenomenon or a statistical aberration, but reflects--at least in part--a more deep-seated, still developing, shift in our economic landscape."

-Alan Greenspan

An actual portrait of Alan Greenspan

The fundamental problem is the growth of worker productivity. Not all of that is due to the growth of technology. It's also because workers are more highly educated and better trained than ever. We're also working more hours. (Part of that has to do with the collapse of unions and the loss of worker power.) And we're also just working a lot harder, and making a lot more stuff. Don't listen, even for a second, to people who claim that millennials are entitled or lazy - they work a lot harder than any previous generation. It's just that, for a variety of reasons, including stagnant wages, hugely increased education costs and massive student debt that cannot be defaulted on, they haven't amassed as much in savings. In the 50s, a male factory worker could be the only member of his family working and make enough money to feed and house his wife and a family of 5. That was the norm. Nowadays, both parents of a smaller family may be working - perhaps more than one job each - and still may not be able to pay the bills.

No major politician is presenting any significant ideas about how to fix this problem. They will blame traditional boom and bust cycles, or they will blame international trade, or immigration. In fact, no major politician is willing even to acknowledge that this problem exists, or to admit that the problem is worker productivity. It seems there’s an entire industry - or group of industries - devoted to deceiving us and distracting us, telling us, “Remain calm. All is well. Move along, folks. Nothing to see here. No gigantic all-consuming black hole at the very center of civilization as we know it! Just look the other way!” And really, it's no wonder that politicians are behaving this way, since the raison d'etre of a politician in a democracy is to address problems that they can, at least theoretically, solve within their term in office. And the problem of worker productivity is so huge and so long-term that it's not at all clear how anyone could fix it. In fact, it's not clear if anyone can fix it, or what that would even mean.

Sadly, politics today is breaking up into two camps - one which pushes for tariffs and other forms of nationalistic protectionism, and the other which is trying to magically turn the clock back to a mythical past of international free trade. No one is willing to stand up and point out that they’re both wrong, and for the same reason- neither of them can open their eyes and face reality, and confront the real problem, which is the meteoric, exponential growth of worker productivity, and the fact that production has expanded so much and so quickly that it has outstripped the capitalist system, which it now shrugs off like the exoskeleton of some molting crustacean.

The Era of TMS

The era of scarcity is ending, and that's somewhat good news. There were a lot of problems in the era of scarcity. But now we are entering another age, the era of TMS: Too Much... (for the delicate ears that might be listening, we'll just make that last word...) Stuff. And that era of TMS has huge problems, too. In fact things may have gotten worse, because at least we know the solution to the problems of scarcity: production. But what are solutions to the problems of TMS?

What are the problems of TMS? Well, first of all: it's not this:

Wipe that from your mind.

But, apart from the question of how to build friendly AI, which I agree with Bostrom and Yudkowsky, is a real problem, with no obvious solution... I see at least (!) four enormous, world-historical problems in the era of TMS:

1. The end of (most? all?) labor

Of course, you might see that as a good thing. Arguing against the utopianism of Ray Kurzweil, I feel a bit like Georges Bataille lecturing Paul Mattick on the "Accursed Share".

2. A crisis in (economic) value

When there's too much stuff, and you can get everything for free, then everything is worthless. Sounds great, right? We'll see....

3. Environmental devastation

This, of course, is the big one.

...but also, last but far from least:

4. The reshaping of imperialism and geopolitics

Each of these problems deserves discussion at length, and I will explore them further in these pages. [Stay tuned: each of the above entries will turn into a link as I write more.] But also, each of these problems is deeply tied up in the other problems, and cannot be understood except in relation to all the rest.

I cannot imagine that it is possible that capitalism will go on forever. On the other hand, it’s difficult for me to conceive of what the world will look like after capitalism. So we seem to be at an impasse. I am certain that capitalism will end. But my question is whether the end of capitalism will also be the end of the human race.

Capitalism isn't simply about mobilizing labor power. Capitalism is another word for free markets, private ownership of productive assets, and decentralized decision making. These things (markets, private ownership, decentralized decisions) are about dealing with *scarcity*.

ReplyDeleteMy guess is that scarcity is not going away. Just a hunch. As some things become more abundant, scarcity persists.

I have to read this and ponder much longer before saying anything else. But I'm still pretty sure that scarcity is not going away.

The other factor is human nature, which probably does exist as a near-constant. The classicist and right wing pundit Victor Davis Hanson likes to talk about his new pump that pumps more water, more cheaply, than his old pump. But the water is still water.

VDH is easy to make fun of but he's onto something. With all the technological transformation, human nature hasn't much changed. There are implications to that fact--but I'm not sure what they are. I think generally it means that some outcomes are more likely than others. Technology may bring us a cornucopian society--but with the same human nature.

I agree that capitalism isn't simply about mobilizing labor power, but I disagree that capitalism is another word for free markets. I think capitalism is the greatest threat to a free market. In fact, I've written about that, here:

Deletehttps://iandowneyisfamous.blogspot.com/2020/11/capitalism-greatest-threat-to-market.html