The Spectacle of Abstention

| |

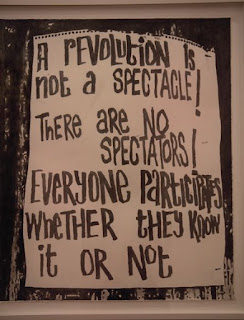

“The revolution is not a spectacle! There are no spectators! Everyone participates whether they know it or not.”

So read an anonymously copied sign, distributed in California, in 1968. It's been often attributed to the Weather Underground but I doubt they wrote it. (If anyone has solid information on the origin of this sign, let me know.)

Anyway, whoever wrote this, they almost got it right.

The better way to put this is: abstention must be understood as a mode of participation in the spectacle.

Yes, there are times when "The only winning move is not to play." But to imagine that this is always true is to succumb to the same kind of dogmatic ideological idealism that abstentionists proudly claim to avoid. There is no a priori schematic set of principles that can tell whether or not to abstain in any particular form of activity; it must be considered in relation to precise historical and material conditions. Beware of claims that any particular conditions will always and forever be true - say, for instance, that we are living in an integrated spectacle from which there can be no escape.

Indeed, the present moment can be understood as one in which the spectacle has utterly absorbed its opposite, and become completely fused with it, so that it has become a spectacle of absence. This characterizes the spectacle as a whole, so that the entire spectacle can be characterized as a spectacle of abstention.

Thus the academic fad that deconstructs the "metaphysics of presence" is entirely useless for analyzing the spectacle in its current formation. In this world, it is not presence that rules, but absence.

The illusion of the spectacle is not what the spectator sees. What the spectator sees is real. The illusion of the spectacle is that there is a spectator, somehow separated from the action, at a safe distance from reality. This is the fundamental romantic notion, akin in some ways to certain Gnostic or other religious traditions, that “the world is not my home,” that I am a stranger, a mere passive experiencer, a person to whom things happen, without ever really being touched by them. But though it may have its own religious pedigree, this pretended worldview is nowhere more present than in science, and particularly the human sciences, such as anthropology, sociology, and criminology, at least in their traditional, classical form, in which the scientist is supposed to adopt a detached, critical, disinterested stance, an attitude of unbiased, opinionless, dispassionate, cool, clear “objectivity.” And this style of reportage is copied from the sciences throughout the academy, into news organizations, other media, hospitals, courts, schools, and even in the workplace. “This does not apply to me,” we tell ourselves, “This kind of thing happens to other people. I am not involved, and I am certainly not to blame for this situation. I am not here.”

Debord writes:

REVOLUTION IS NOT “showing” life to people, but bringing them to life. A revolutionary organization must always remember that its aim is not getting its adherents to listen to convincing talks by expert leaders, but getting them to speak for themselves, in order to achieve, or at least strive toward, an equal degree of participation.

Thus Debord, in Society of the Spectacle and elsewhere, warns his readers extensively about various forms of "pseudo-participation," and some of the dirtiest words in his vocabulary are "specialist" and "expert" - so much so that one can easily get the impression that the spectacle simply is these "convincing talks by expert leaders. But a more fundamental illusion is the illusion of non-participation, the illusion that non-participation is possible - an illusion to which Debord himself was sometimes susceptible.

Kafka sums it up well: even if the street was not getting any further away from the castle, it was not getting any nearer to it.

REVOLUTION IS NOT “showing” life to people, but bringing them to life. A revolutionary organization must always remember that its aim is not getting its adherents to listen to convincing talks by expert leaders, but getting them to speak for themselves, in order to achieve, or at least strive toward, an equal degree of participation.

Thus Debord, in Society of the Spectacle and elsewhere, warns his readers extensively about various forms of "pseudo-participation," and some of the dirtiest words in his vocabulary are "specialist" and "expert" - so much so that one can easily get the impression that the spectacle simply is these "convincing talks by expert leaders. But a more fundamental illusion is the illusion of non-participation, the illusion that non-participation is possible - an illusion to which Debord himself was sometimes susceptible.

Kafka sums it up well: even if the street was not getting any further away from the castle, it was not getting any nearer to it.

Throughout the entire spectacle, there are abstentions, and abstentions upon abstentions, branching off into complexities that would make a Byzantine theologian blush. In societies wherein modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of abstentions.

The more one abstains - from meat-eating, from animal-product-using, from consumption, from voting, from activism, from a career, from family, from war, from imperialism, from capitalism, from life - the more thoroughly enveloped and enmeshed in the spectacle one becomes.

Those who loudly proclaim that they are exiting the spectacle in any of its forms - from nihilist artists to the boomer who angrily posts that they are leaving a facebook group - are literally making a spectacle of themselves.

The spectacle of abstention thus is the strange doppelganger, the mirror image of the spectacle of expertise. The spectacle of expertise is the sloughing off of the necessity of theory, onto an other (the expert) who - theoretically - will do the theorizing. One may therefore think that the spectacle of expertise is all practice, no theory, while the spectacle of abstention is all theory, no practice. But this is an incomplete analysis. In reality, it is not true that the spectacle of abstention is no practice. It, too, is practice. But the very fact that it is conceived as non-practice is a symptom of the insufficient theory, rather than a lack of practice.

Furthermore, abstention is often - but not always - an ineffective strategy. It was easy, for instance, for westerners to look from the sidelines of the 2004 election in Iraq and to say that the largely Sunni Iraqi Islamic Party's decision not to participate in that election was a tactical blunder, seeing as this cost them the opportunity to frame the constitution of 2005. But at least they had worked for decades to become the powerful political party that they were and are, and so at least their abstention was in some sense consequential, unlike the kind of abstention that is called for by certain leftists in the west.

Many forms of this illusion occur among activists,

particularly those on the "radical left." It is assumed that by not

forming a party that nominates candidates for positions in the

government, that one is managing not to participate in

parliamentarianism. It is blithely assumed that by not joining the

Democratic or Republican parties, one has become “independent.” It is

assumed that by not explicitly joining and paying dues to a

pseudo-radical organization such as SAlt or the RCP, that one

has magically separated oneself from these organizations and their

destiny. Likewise we imagine that we are somehow “outside” of the

Church, simply because we do not attend it. People who never shopped at Walmart announce that they are “boycotting”

Walmart, and thereby absolve ourselves of

responsibility for Walmart’s actions, and so on. But this very notion

of separation is itself an illusion, an illusion created by a rather

weak analogy with the commodity form and consumer culture.

The spectacle of abstention does not mean, simply, not doing something. In a trivial sense, everyone "abstains" from an uncountable multiplicity of possible actions simply by doing anything else. Of course the real movement for the overthrow of the present conditions of life will choose tactically to take certain actions and not to take others, at various times, depending on material conditions. But abstention becomes integrated into the spectacle when it contributes materially to the false consciousness of an identity conceived as being separate, apart from what are conceived as unenlightened masses and their misguided movements - political, cultural, religious, what have you - and especially when this consciousness, this identity, this role, is then broadcast to the world in a self-presentation that is its own form of pseudo-participation.

To take this further, the intellectuals that advocate for abstention are, themselves, experts of a kind - specialists in abstention. They have almost rendered themselves into pure spectators - almost, but not quite, of course. For they also must pass on their little "observations" to us, their public. They are not pure spectators, but they want us to fall into pure spectatorship, to absorb and apply their lofty teachings like good little disciples. All of their books could be re-titled "How to Stay Clean". Of course, if we were really to absorb their lessons, we would ultimately decide to abstain - from their own teachings. Taking this historical movement to its necessary conclusion, we become living contradictions, which embody the deeper and broader contradictions of liberal society as a whole.

The spectacle of abstention does not mean, simply, not doing something. In a trivial sense, everyone "abstains" from an uncountable multiplicity of possible actions simply by doing anything else. Of course the real movement for the overthrow of the present conditions of life will choose tactically to take certain actions and not to take others, at various times, depending on material conditions. But abstention becomes integrated into the spectacle when it contributes materially to the false consciousness of an identity conceived as being separate, apart from what are conceived as unenlightened masses and their misguided movements - political, cultural, religious, what have you - and especially when this consciousness, this identity, this role, is then broadcast to the world in a self-presentation that is its own form of pseudo-participation.

To take this further, the intellectuals that advocate for abstention are, themselves, experts of a kind - specialists in abstention. They have almost rendered themselves into pure spectators - almost, but not quite, of course. For they also must pass on their little "observations" to us, their public. They are not pure spectators, but they want us to fall into pure spectatorship, to absorb and apply their lofty teachings like good little disciples. All of their books could be re-titled "How to Stay Clean". Of course, if we were really to absorb their lessons, we would ultimately decide to abstain - from their own teachings. Taking this historical movement to its necessary conclusion, we become living contradictions, which embody the deeper and broader contradictions of liberal society as a whole.

For the logic of abstention is a liberal logic. It assumes autonomous agency, discrete action, and a meaning for action that is symbolic and representational - ideological, rather than material. From the materialist perspective, that is to say, from the outside, abstention looks a lot like silence, quietism, acceptance, abject submission. What is the difference between quiescence and abstention? It is only an ideological difference.

Comments

Post a Comment